Ultimate Hegelian Reading List

NOTE: The image is slightly out of date compared to the table below. I have since added: Pico’s Oration, Aquinas Selected Writings, Epictetus’s Discourses, Boethius’s Consolation of Philosophy, Augustine’s City of God, and some others.

|

No. |

Year |

Cover |

Author |

Title |

Notes |

|

1 |

500 BC |

|

Parmenides |

On Nature |

Philosophy begins with Parmenides. He raises the question of thinking and being, and formulates the principle of identity: “this shall never be proved, that the things that are not are.” |

|

2 |

490 BC |

|

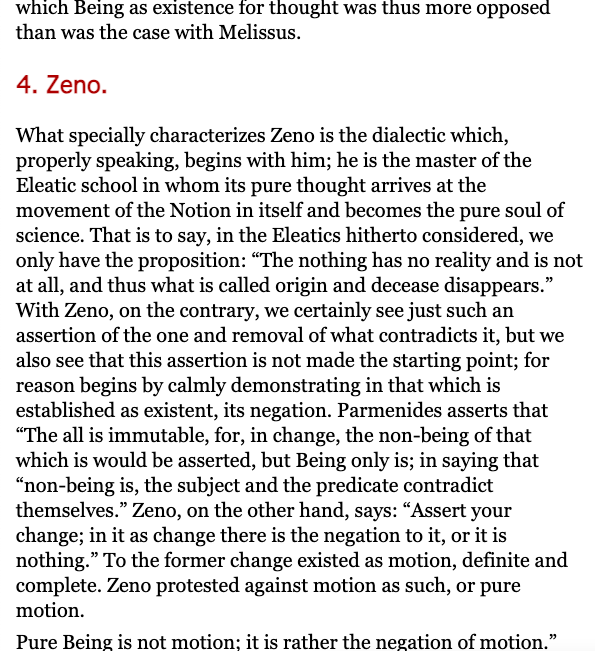

Zeno |

Paradoxes |

On account of his paradoxes, Parmenides’s student, Zeno is known as the father of dialectic. His writings have not come down to us. But Hegel gives a helpful overview of the paradoxes in his Lectures on the History of Philosophy. |

|

3 |

500 BC |

|

Heraclitus |

Fragments |

Hegel said that “there is no proposition of Heraclitus which I have not adopted in my Logic.” The thought of flux or becoming is most associated with Heraclitus, but the fragments on Logos are just as essential. |

|

4 |

380 BC |

|

Plato |

Republic |

Plato’s masterpiece. Book VI is especially notable, because it contains the allegories of the sun, divided line, and cave. The remark at 509b, that “the good is beyond essence [ousia],” is also to be noted. |

|

5 |

360 BC |

|

Plato |

Theaetetus and Sophist |

Sophist is an ontological inquiry like Plato’s Parmenides and Aristotle’s Categories. It serves as a propaedeutic to them both. It may be paired with the Theaetetus, an epistemological dialogue with similarities to Descartes’s Meditations. |

|

6 |

360 BC |

|

Plato |

Philebus |

This dialogue contains an important discussion of the finite and the infinite (peras and apeiros), which comes from Anaximander, the pre-Socratic. |

|

7 |

360 BC |

|

Plato |

Parmenides |

Parmenides is Plato’s theology. The dialectic here is really a derivation of the categories. The One is the first god, or the Father. The discussion with Parmenides and Zeno is an instruction for us to think the ideas (forms) in and for themselves. |

|

8 |

360 BC |

|

Plato |

Timaeus |

End Plato with the Timaeus, which discusses the other two gods, the Demiurge or Son, and the World Soul. The discussion of the formation of the world at 31b is notable. I recommend the Cooper translation for all of Plato’s works. |

|

9 |

335 BC |

|

Aristotle |

On the Soul |

Hegel: this is “perhaps the only work of philosophical value on this topic.” Soul is the form of body. And it is activity: it only is when it thinks (cf. Fichte). Actuality is thus the true substance. Mind is passive or active. The latter is immortal. |

|

10 |

350 BC |

|

Aristotle |

Categories & On Interpretation |

The Categories are the universal determinations of beings qua being. They are equally logical and metaphysical. They recur in the Metaphysics and the inquiry into them is revived by Kant. On Interpretation is the theory of judgment. |

|

11 |

350 BC |

|

Aristotle |

Prior Analytics |

This is Aristotle’s theory of the syllogism. This is a formidable work, and at times tedious. But it is the first inquiry of its kind. No one before Aristotle attempted a doctrine of thinking in its concrete actuality. |

|

12 |

330 BC |

|

Aristotle |

Metaphysics |

Read Zeta, Eta, Theta, Lambda. Substance is not matter, but essence (to ti en einai) or form. Actuality is thus prior to potency. But actuality is thinking. Substance is thus subject. Absolute substance is restful act, thought thinking itself, God. |

|

12a |

50 AD |

|

Philo of Alexandria |

Works of Philo |

Philo was a man of great learning, who laid the foundation for the integration of Platonism with Christianity. Notable in this regard is his essay, ‘On the Creation’, which is a mystical (i.e. speculative, philosophical) elucidation of the Book of Genesis. |

|

13 |

90 AD |

|

Orthodox Study Bible |

Especially important in the Old Testament are: Genesis, Exodus, Kings, Wisdom of Solomon, Job, Proverbs, the Greater Prophets. In the New Testament: Gospel of John, Paul’s letters, John’s letters, and Revelation. The serpent does not lie to Eve in Genesis. God states the principle of identity a la Parmenides in Exodus 3:7-14. |

|

|

14 |

108 AD |

|

Epictetus |

Discourses |

This is the greatest work of Stoicism. And Stoicism is the philosophy that coincides with the New Testament. Epictetus’s Discourses and Enchiridion are amazing and not to be passed up. Stoicism had a great influence on German Idealism and Hegel especially, for its strong affirmation that Nous / Logos governs the world. This is what we find in John 1:1, which is a reference to Stoicism, which got the Logos principle from Heraclitus. |

|

14 |

150 AD |

|

Justin Martyr |

First & Second Apology |

These are excellent essays in Christian apologetics that are simultaneously Platonist. Martyr does not hesitate to say that Plato and Aristotle were divinely inspired, and he presumes no discontinuity between philosophy and religion. |

|

15 |

190 AD |

|

Clement of Alexandria |

Stromateis |

Clement sets forth ‘gnostic Christianity’. But for Clement, ‘gnosis’ is simply the Christian revelation. It does not have the negative, dualistic connotation we associate with it. Hegel’s library contained all of Clement’s works. |

|

16 |

230 AD |

|

Origen of Alexandria |

On First Principles |

The first comprehensive Christian theology. It is a Platonic theology. Notable here is the idea of universal salvation or apokatastasis. This finds its way to Hegel through St. Maximus, Eriugena, Böhme, and Oetinger. |

|

17 |

200 AD |

|

The Corpus Hermeticum |

This is like the Bible of Platonism. The books are read by many Christian theologians, Neoplatonists, and Renaissance humanists. It comes to Hegel via Ficino, Agrippa, Bruno, Paracelsus, and Böhme. Identity of knowledge and freedom is present here. |

|

|

18 |

270 AD |

|

Plotinus |

Enneads |

This lacks the systematicity of Proclus. Yet it’s notable for impact on later Christian theology. Especially the essay, ‘On the Three Principle Hypostases’. God is three: the One, Intellect, and Soul. Proclus rethinks these as negation of negation. |

|

19 |

380 AD |

|

Gregory of Nyssa |

On the Soul and Resurrection |

Gregory of Nyssa is the most Origenist, and thus Platonic, of the Cappadocian Fathers. This text is worth reading, because here there is no distinction made between knowledge and mysticism. Nyssa is not squeamish about attempting to know divine truths rationally. This text also influened Maximus the Confessor, who is also very Origenist. |

|

20 |

450 AD |

|

Proclus |

Commentary on Plato’s Parmenides |

Great intro to Platonism as a whole, and thus to Elements of Theology. He says dialectic is divine science and the only salvation! Read Introduction + books 5-7. Important here is the discussion of the varieties of negation. |

|

21 |

450 AD |

|

Proclus |

On the Theology of Plato |

Hegel considers this to be Proclus’s masterpiece. Especially important are Books II and III where Proclus unfolds his triadic system. |

|

22 |

450 AD |

|

Proclus |

Elements of Theology |

Proclus’s masterpiece. All of metaphysics is here in the form of negation of negation. The spiritual method is procession (proodos) and reversion (epistrophe). Hegel says it’s the turning point from ancient to modern (Christian) times. |

|

23 |

500 AD |

|

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite |

The Divine Names |

This man introduces Proclus’s negation theory to Christianity. It is essentially Proclus + Christian piety. Now begins the odyssey in which philosophy loses itself in theology, and does not return to itself until Descartes. |

|

26 |

630 AD |

|

Maximus the Confessor |

Ambigua |

Maximus is like the Byzantine Böhme. Here we find the idea of apokatastasis paired with some genuine insight into the negation of negation. Ambigua 17, 20, 41, and 42 are most important. |

|

27 |

634 AD |

|

Maximus the Confessor |

Responses to Thalassios |

Maximus’s mystical theology presented as answers to questions on difficulties in scripture. |

|

28 |

862 AD |

|

Eriugena |

Periphyseon |

Eriugena was instructed to continue Maximus’s work by Charles the Bald. The very beginning, where he discusses the division of nature, is interesting with respect to Hegel. He may be called the Medieval Hegel. There is an angelology here as well. |

|

28 |

1000 AD |

|

Various Writers |

The Philokalia |

This is the compilation of mystical hesychast texts of the Eastern Orthodox tradition. Especially notable is Volume 4, the texts by Symeon the New Theologian, Nikitas Stethatos, and Gregory Palamas. Stethatos’s ‘On the Inner Nature of Things’ and ‘On Spiritual Knowledge’ are very good. |

|

29 |

1077 AD |

|

Anselm |

Proslogion |

To understand Hegel one must know his defense Anselm’s argument for God’s existence contra Kant’s criticism that being is not a predicate. For Hegel, Anselm’s argument means that the concept necessarily has being in it. Or thinking and being are one. |

|

36 |

1310 AD |

|

Meister Eckhart |

Selected Writings (Sermon 17) |

Eckhart knew Eriugena. He says “The eye through which I see God is the same eye through which God sees me.” The Church made him a heretic. He inspired Luther via Tauler. Sermon 17 in this volume contains a discussion of the negation of negation. |

|

36 |

1340 AD |

|

Johannes Tauler |

Sermons |

Tauler is a disciple of Meister Eckhart and a great influence on Martin Luther. |

|

37 |

1341 AD |

|

Gregory Palamas |

Triads |

Palamas is only superficially anti-rationalist. Closer inspection reveals that he rejects lower forms of reasoning, and what he considers to be ‘beyond reason’ is what Hegel calls speculative reason. Especially notable here is the thought of theosis as ‘becoming uncreated’ - this is very Hegelian. |

|

38 |

1482 AD |

|

Marsilio Ficino |

Platonic Theology |

Ficino is important because he is responsible for the translation of all of Plato’s works into Latin for the first time. This is an undeniably cataclysmic event for science, because now the mystical element, i.e. the dialcetical element, of thought and reality is rediscovered after an 800 year hiatus. The recovery of Plato reveals the futility of Scholasticism and its casuistry, and also reconnects the Western world to the East. The story is that Cosimo de’ Medici made Ficio the head of his Academy in Florence, thus connecting the work of the Byzantine scholar Gemistos Pletho to the West via Ficino’s translation and commentary work. He also translated the Corpus Hermeticum into Latin and was inspired by Proclus. He himself inspired Girodano Bruno. ‘Platonic Theology’ is Ficino’s major work. We see mysticism attempting to return to the West. But it is only an attempt. |

|

39 |

1486 AD |

|

Pico della Mirandola |

Oration on the Dignity of Man |

Pico delivers an oration infusing hermeticism, Greek philosophy, Christianity, and Jewish Kabbalah. |

|

40 |

1517 AD |

|

Johann Reuchlin |

On the Art of Kabbalah |

This influential work contains a very intriguing quote at the end of Book I, citing a text called ‘On Faith and Atonement’. |

|

42 |

1584 AD |

|

Giordano Bruno |

Cause, Principle, and Unity |

The Church martyred Bruno due to his heliocentrism. His writings exhibit an advanced dialectic, deeply inspired by Cusanus, who also knew Eriugena. Bruno’s dialectic is among Hegel’s great inspirations. Schelling wrote a book on him. What is perhaps Bruno’s most important work with respect to Hegel, where he elaborates a triadic system in the manner of Proclus, is called De triplici minimo et mensura (On the Triple Minimum and Measure). But it is not available in English as far as I can see. This is the point where is most relevant to German Idealism and to genuine philosophy in general. |

|

43 |

1605 AD |

|

Johann Arndt |

True Christianity |

Excellent mystical and ascetical text in the Lurtheran tradition that influenced Russian Saint Tikhon of Zadonsk. |

|

44 |

1612 AD |

|

Jakob Böhme |

Aurora |

Hegel calls Böhme ‘the first German philosopher’. Aurora is a Christian theosophy with terms from Paracelsus, a great healer. Aurora influenced Oetinger’s apokatastasis. The chapter on Böhme in Hegel’s History of Philosophy elucidates this obscure work. |

|

44b |

1619 AD |

|

Jakob Böhme |

Three Principles of the Divine Essence |

Another of Böhme’s important works, describing God as an interconnected unity of three principles. |

|

44c |

1620 AD |

|

Jakob Böhme |

On The Threefold Life of Man |

The last of Böhme’s most important works. |

|

44c |

1641 AD |

|

René Descartes |

Meditations |

Philosophy returns to its native soil with Descartes’s Meditations for the first time since Proclus. Thinking and being are substances, res cogitans and res extensa. They are connected through God but this unity is not developed by Descartes. |

|

45 |

1663 AD |

|

Baruch Spinoza |

Principles of Cartesian Philosophy |

Spinoza’s elucidation of Descartes, and the beginning of his own system. What is most interesting here is the appendix, the Cogitata Metaphysica, where Spinoza writes, “we begin, therefore, with being.” |

|

46 |

1677 AD |

|

Baruch Spinoza |

Ethics |

Spinoza’s masterwork. Thinking and being are attributes of one substance, ‘God or nature’. The defect is that substance is unspiritual, unfree. Yet the German Idealists are so influenced by Spinoza that their system may be called ‘Spinozism of freedom’. |

|

47 |

1689 AD |

|

John Locke |

Essay Concerning Human Understanding |

The most important work of English philosophy. It is not very good, in keeping with the character of English philosophy in general. But it is still important as a stepping stone to Kant, because Kant needs the English empiricist principle, namely of Bacon, to get to the high point of consciousness he attains. Kant is an enormous genius and to understand him we must read some of this. This also helps us learn to translate between English and German. |

|

53 |

1712 AD |

|

The Pietists |

Selected Writings |

The Pietists were influenced by Jakob Böhme, and they constitute basically the spiritual milieu of Hegel’s youth. Oetinger, who advances a kind of apokatastasis, is translated in this volume. In this volume are worth reading, Bengel and Oetinger. |

|

48 |

1714 AD |

|

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz |

Discourse on Metaphysics & Monadology |

If Spinoza makes the universal the principle, and Locke makes it empirical multiplicity, then Leibniz unites the two in the individual, the monad. His ‘monadology’ is influential. But ‘pre-established harmony’ does not solve Spinoza’s freedom problem. |

|

48 |

1714 AD |

|

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz |

Theodicy |

This text was really influential on German Idealism. Leibniz defends God’s Providence. |

|

49 |

1720 AD |

|

Christian Wolff |

Rational Thoughts on God |

Wolff lays down the Leibnizian philosophy in the German tongue. Thus it is called the Leibniz-Wolff system. Hegel read Wolff’s ‘Logic’ as a student. But the more important text is ‘Rational Thoughts on God’. Chapters 1-3 + 6 are notable. |

|

50 |

1739 AD |

|

Alexander Baumgarten |

Metaphysics |

Kant taught from this textbook for much of his career. It is the Leibniz-Wolff system, but more organized. Roughly, the content of Hegel’s system is here, but in dogmatic, undialectical form. Kant negates Baumgarten, Hegel negates the negation. |

|

51 |

1764 AD |

|

Crucius and Lambert |

Kant Source Materials |

From this volume read the essay by Crucius, ‘Sketch of the Necessary Truths of Reason’. And by Lambert, ‘Treatise on the Criterion of Truth’. These texts shed light on Kant’s Critique of Reason. Lambert was sponsored by Frederick the Great. |

|

52 |

1779 AD |

|

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing |

Philosophical and Theological Writings |

Lessing is a major figure of the German Enlightenment. The most important text in this volume is ‘The Christianity of Reason’. This is German Idealism in a nutshell or in concept. The conversation with Jacobi is influential. |

|

54 |

1800 AD |

|

Immanuel Kant |

Logic |

The whole content of Hegel’s Science of Logic is right here, but in a totally unsystsematic, undeveloped form. If one takes all this subject matter and carefully develops each element from another, so that the whole has the form of abiding, proceeding, reverting, then that is precisely Hegel’s Science of Logic. |

|

55 |

1781 AD |

|

Immanuel Kant |

Critique of Pure Reason |

Synthesis a priori = thought is concrete in itself. Dialectic finally known as necessary. Categories are the forms of Judgment à la Aristotle. Read: Clue for the Discovery, Intro to Division Two, Concepts of Pure Reason, Ideal of Pure Reason. |

|

56 |

1783 AD |

|

Immanuel Kant |

Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics |

Excellent summary of the prev. In dialectic, thought touches the void beyond the bound of reason. Dialectic = divine science. But problem: Kant has the ghostly thing-in-itself hanging around. Hegel shows the paradox = God. |

|

57 |

1788 AD |

|

Immanuel Kant |

Critique of Practical Reason |

Theory of will on scientific basis. Reason is here independent. It has the moral law (Lev. 19:18), which is freedom (John 8:32). But in Kant it is abstract. Because for Kant God is postulate only. Cf. Hegel, Philosophy of Right, §135. |

|

58 |

1790 AD |

|

Immanuel Kant |

Critique of Judgment |

Reason was restricted. But there remains a demand to overstep the bound. The Idea must be concrete. Because teleology in nature requires unity of reason and experience. Yet Kant retains the dualism. Read § 64-71, 77-78, and 82-86. |

|

59 |

1794 AD |

|

Johann Gottlieb Fichte |

Concerning the Concept of the Wissenschaftslehre (in ‘Early Philosophical Writings’) |

This text is very helpful for understanding Fichte’s Wissenschaftslehre. Hegel cites it in his lectures on the history of philosophy. |

|

60 |

1794 AD |

|

Johann Gottlieb Fichte |

Science of Knowledge (Foundation of the Entire Wissenschaftslehre) |

Hegel says “from Aristotle to Fichte, no one thought to derive the categories.” It is the I = I or conscious identity principle, which is the key to the activity of the deduction. Cf. Exodus 3:14. With Fichte the thing-in-itself hangs around. |

|

61 |

1795 AD |

|

F.W.J. Schelling |

On the ‘I’ as Principle of Philosophy |

Schelling’s early Fichtean system. This is good for beginners. Dialectic breaks out of the subjective status and the thing-in-itself is known as the ‘I’. But the ‘I’ is ambiguous: finite or infinite (divine) ego. |

|

63 |

1800 AD |

|

F.W.J. Schelling |

System of Transcendental Idealism |

Dialectic approaching Hegel’s Logic. Three epochs match roughly the three books of Hegel’s Logic. Thing-in-itself overcome? Two problems: the Absolute is defined as an ‘indifference’, and the dialectic ends in aesthetics. |

|

64 |

1801 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Differenzschrift |

Early text on Hegel’s criticism of Fichte and Schelling, and thus offers clues into the development of Hegel’s Absolute System. The whole content of science must be lifted up into the I = I or identity principle of consciousness. Including nature. |

|

64a |

1804 AD |

|

J.G. Fichte |

The Philosophical Rupture between Fichte and Schelling |

A selection of correspondences that elucidate the rupture between Fichte and Schelling, which influenced Hegel’s Logic. |

|

64a |

1804 AD |

|

J.G. Fichte |

1804 Lectures On The Wissenschaftslehre |

Fichte’s notable later lectures on his Wissenschaftslehre. |

|

65 |

1805 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Jena System |

This early version of the Logic shows Hegel struggling to structure his system. It is useful as a point of reference for the Logic’s development. Much of the final work is here already, but the whole is not quite in the form of negation of negation. |

|

66 |

1826 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Lectures on the History of Philosophy |

In preparation for the end, please read some chapters from these lectures. The most important are: Zeno, Plato, Aristotle (especially!), Proclus, Bruno, Böhme, Spinoza, Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Final Result. |

|

67 |

1817 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Encyclopedia Logic |

The introduction of this text is especially recommended for beginners. In Being, the relation between categories is immediate. In Essence, they are showing themselves in an other. In Concept, they are self-comprehending. |

|

68 |

1817 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature |

Introduction is good for beginners. Divisions of nature (Mechanics, Physics, and Organics) reflect those of Logic (Being, Essence, and Concept). Plants and animals have the form I = I, principle of identity, self-comprehension. |

|

69 |

1817 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Encyclopedia Philosophy of Spirit |

Likewise here Being is Subjective Spirit, Essence is Objective Spirit, and the Concept is Absolute Spirit or infinitely free and self-determining Spirit. The content is similar to the Phenomenology, but this is more organized. |

|

70 |

1807 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Phenomenology of Spirit |

This work was wrongly taken in the 20th century, in France, to be Hegel’s whole system. In fact it is a propaedeutic. Taken as a whole unto itself, the result is a terrible relativism and abstract liberalism. The preface and introduction are famous. |

|

71 |

1821 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Philosophy of Right |

This book is a masterpiece. Abstract Right corresponds to the problem of property, or communism (Marx). Morality likewise corresponds to fascism (Nietzsche). Ethical Life is the synthesis of the two, or genuine Hegelian liberalism. |

|

72 |

1818 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Lectures on Logic |

Translator made some odd decisions but the lecture is good. Clarifies some obscurities in the Greater Logic. The last 20 pages or so are especially good. p. 228 is interesting vis-à-vis Orthodox Trinity (cf. Romanides ‘Franks, Romans…’). |

|

73 |

1822 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Lectures on the Philosophy of World History |

Famous series of lectures Hegel gave at University of Berlin. Especially relevant is the section on the Reformation. One should look here for Hegel’s essential criticisms of Catholicism and abstract (negative) liberalism. |

|

74 |

1827 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion |

Christianity is the Absolute Religion. In the introduction and first part (on the Concept of Religion) are found some of Hegel’s clearest and most direct statements about God, the Absolute Idea in relation to Absolute Spirit. |

|

75 |

1829 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

Lectures on the Proofs of the Existence of God |

The three proofs of God’s existence (ontological, cosmological, and teleological) correspond to the three spheres of Logic, Nature, and Spirit respectively, and to the three persons of the Christian Trinity. |

|

76 |

1816 AD |

|

G.W.F. Hegel |

The Science of Logic |

Hegel’s masterpiece. No one since Hegel has reached this high degree of penetration into the truth. Marx and Nietzsche are the sundered sides of this infinite self-comprehending unity. The World Spirit labors in darkness. |